Casting a measured gaze across the pages before him, August Schleicher turned away, removed his spectacles and rubbed his eyes. A few moments passed and he turned back toward the desk. Setting to work he muttered, “I walk in a field of ruins”.

The variants in the texts that lay before him, sprinkled in some places, and densely clustered in others, evidenced decline from an original that he had made his life work a process of recovering.

Language was an organism awaiting reconciliation to a line of descent.

Unlike Darwin he did not subscribe to the notion that descent entailed a concomitant relationship to ascent. Schleicher’s concept of descent was tied to decay, “in sound and in form”. It was crucial to recover the origin of language through the reconciliation of a decidedly decadent view of variance. How else would one go about reassembling the ruins?

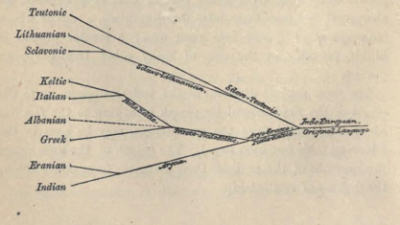

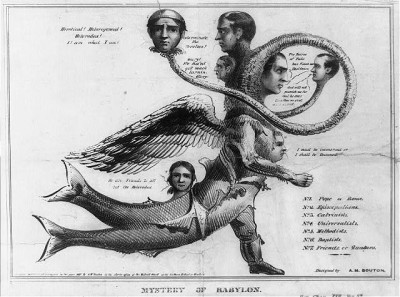

August Schleicher came to the fore as a philologist during a time in which the mettle of a discipline was measured by its ability to prove itself as a science. Bernard Cerquiglini marks the scientific turn in medieval philology 1860 – 1913. Systematic combing of archives and libraries led to the definition of a vast corpus characterized by theretofore unseen levels of variation. A range of institutional support cropped up to advance novel approaches to this newly broadened vision of manuscript resources. Chairs of medival philology at universities, societies like the Societe des Anciens Textes Francais, and organizations like the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes came into being. In Germany, Schleicher and his contemporaries were some of the first philologists to use the Stammbaumtheorie, or “Family-Tree Theory” to visually chart the development of and relationship between languages. They classified languages remnant in the manuscript resources, pursuing reconstruction of origins. Cerquiglini describes the effort as a, “Visionary reconstruction . . . in the shape of a tree fraught with lopped off boughs where improbable monsters sheltered their wretched, disparate nature.”

Through his work on textual criticism Karl Lachmann was perhaps chief among the monster hunters. Whereas Schleicher sought to find the roots of language, Lachmann reconciled variance to establish the origin and authenticity of texts. The coupling of these concepts is important because they form the foundation of claims to authority be they religious, cultural, or legal. The determination of authoritative texts, then and now, is a difficult endeavor. Humans with their annoying tendency to commit errors in the printing process, with their imperfect memory, and their untroubled decision to let subjectivity shine through the editing of texts, casts a pall over efforts to discover a version of a text that is both original and authentic…authoritative. All of these human factors make being a philologist tough work.

Lachmann favored recensio, or comparative study of several manuscripts, to emendatio, or focused study of a single manuscript. Lachmann started from the principle that it was highly unlikely that multiple manuscript copyists could make the same error in the same place of the manuscript by chance. Shared errors across many manuscripts indicated an inherited defect and a form of filiation to an archetype. A single variant manuscript resource, that stood out from a corpus, was held to be an isolated mistake- an aberrant deviation from the original. Wending his way through many manuscript resources, identifying shared variants or “errors”, Lachmann charted dependent relations between manuscripts, reconstructing them in a treelike hierarchical form. Single variants that could not be compared were excluded as inauthentic errors in the development of a manuscript across time and space.

This obsession with the reconciliation of manuscripts was rooted firmly in a decadent view of variance – all variation was held to indicate decay. This reclamation of origins and fixation on establishing the authenticity of texts stands in stark contrast to the perception of these values during the time in which the texts were produced. Simply put, notions of originality, authenticity, and text had different meanings for the creators. Borrowing heavily from Cerquiglini, as I have throughout this piece, scribal culture involved the production of texts copied by hand – a drawn out process that invited manipulation, annotation, commentary. To illustrate Cerquiglini’s thoughts on the concept of the text itself I think its best to quote him at length:

Starting in the eleventh century . . . textus was used more and more exclusively to designate the codex Evangilorum. Attested around 1120, the French word tiste, changed then to texte . . . meaning the “book of Gospels”. This text was the Bible, the immutable word of God . . . an utterance that is stable and finite, a closed structure: textus (the past participle of texere) was something woven, braided . . . it was a weft, a framework. The past perfect form of the verb tisser, textus possessed a connotation of fixity . . . which textuary thought would then provide with full semantic power . . . medieval writing . . . was a reprise; it put things together, constantly and again and again wove works.

Narrative content was relatively fixed.

The originality of a work lay not in the content but the form and the commentary that accrued to it.

This is an appreciation of sameness delivered at different cadences.

19th century understandings of origins and authenticity emphasized by men like Lachmann elide what variation meant to the creators of the objects under study, and likely what qualities determined their value. Commentary, modification in form, and other manipulations were the hallmarks of creativity, of originality, of authenticity. Embracing the creators’ notions of what variance meant could help us get around current apprehensions over the determination of the origin and authenticity of digital objects.

Variance need not be coterminous with deviance.

Cathy Marshall has repeatedly shown, that much of the anxiety attendant to discussions about digital objects revolves around perceived threats to ownership rights. Cathy’s research indicates a wide range of complicated and apparently conflicting views on how digital objects can and cannot be used by individuals other than the creator of the digital object. Reflecting upon her research Cathy noted individual understanding of, “Ownership often extends beyond literal boundaries, governed by a complex interweaving of ethics, need, and naïve © law.” This interweaving was found to be readily apparent when examining the effect of “social distancing” on individual understandings of what constituted appropriate reuse of content.

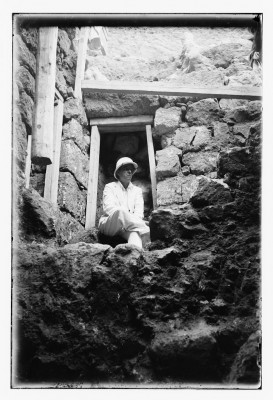

Think about it. How do the following creation factors – “by me”, “of me”, “of a place Ive been” – effect your thought about how other people can reuse digital content you have created?

Ownership rights are ultimately tied to claims of origin and authenticity. You assert your ownership rights based on the fact that you created it. You might prove, or authenticate this through any number of means. After collecting and evidencing the authenticity of your digital object, your authority is manifest in your ability to control how, why, and where it is reused. In theory.

In practice, control over digital content is slippery. Codification of user rights that take into account remix and reuse of digital content as a relative norm have arisen to help charter a vision of ownership relevant to how digital objects are used in everyday practice. Creative Commons licenses have the capacity to protect and release control over content. The licenses are easy to understand yet provide finely variegated levels of control and release over digital content. Creators can open up their work to remix and reuse, for noncommercial and commercial purposes, all the while requiring at least a base level of attribution. See the variety of Creative Commons licenses for more information.

Variance does pose an interesting problem for individuals and organizations trying to make decisions about what digital content to save, when the stability of that content is relative to the amount of creativity exacted upon it by a global audience. For an individual I imagine that the decision of how to reconcile variance is a bit easier. Personal choices can be less self consciously subjective choices – the consequences of your decisions are your own.

I upload a photo to Facebook. Or Flickr. On Facebook I receive some likes and a few comments. Perhaps the photo will spark a memory for one of my friends and they comment. Another friend remembers things differently and says so in the comment string. An argument ensues and two friends have a very public falling out. While this chain of events is imagined Im sure most people who use Facebook can recount a similar experience. On Facebook the photo has become more than a photo. It has also become a snapshot of my network of relationships and how they relate to one another. Do I save this photo with the comment string included? Do I save the “original” photo that sparked the conversation? How useful does it continue to be to regard the photo I uploaded to Facebook as the original? The origin of that photo – my iPhone – is likely not important to the people who commented on it on Facebook. For them Facebook is the origin. So in this context I might relocate the “original” quality of the photo to Facebook and save that conversation. Or I might, in a fit of anxiety ridden personal archiving just save everything – the “original” photo from the iPhone, ” the “original” photo on Facebook, and the conversation generated by it.

Respectively I would be preserving the object with the highest image quality, and the lower quality image with the conversation attached to it. I dont place these objects into a hierarchy based on origin. The value of the objects lies in their variance – a variance whose reconciliation through a hierarchical system of relations that emphasizes the value of origin would put digital objects into false competition. For me, preserving my digital objects in their variant forms is tied more to meaning rather than trying to root out origins – which object begat the other is not the central value I seek.

To take a moment and think before reconciling variation is to take a step toward preserving the multiplicity of expression that is the human experience. This is not to say that it is not necessary to make choices about what digital objects to toss away. Rather Im suggesting that using origin and the twin quality of the authentic as a rubric of value may be less relevant to a world in which our digital objects take on a life of their own – trafficked across social networks and the web at large – they are endlessly subject to the creative potential of our peers.